The studio had been completely transformed. No longer, a workspace, it had become a white cube overgrown with tondi.1 Nearly all the walls were covered with small circular works, while larger circular paintings were also hanging or leaning against some of the walls (Figure 1). Rather than in a studio, I found myself in a combination of installation and storeroom from which new exhibitions could be initiated. And this was indeed about to happen, as Ton Mars was just then preparing for his Tondi exhibition that would open on 2 October 2013 at Daniela & Cora Hölzl Kunstprojekte in Düsseldorf.

I had never seen so many tondi by the same artist in one room.2 The small ones were mostly dark in hue and covered the walls in strict ranks. All were ‘inscribed’ with white signs and thus resembled each other but I was unable to discern the meaningful relationship between all these circular shapes. The large tondi were painted in primary colours or in black and white and formed two groups. The mood of the first group (in red, yellow, blue and other colours) was more festive and earthbound than that of the second group (one panel in white, one in black and two in shades of blue) which showed a cool and somewhat distant world.3 I experienced their visual impressions as stimulating, while I also felt that I had to reflect more deeply on this development in Ton Mars’s oeuvre. But it was so new to me that I could hardly get to grips with it.

Figure 2

It wasn’t that the artist had only begun making tondi in 2013, however. He had created his first circular composition as early as 2003: Fenster, a circular window in the home of Thomas and Isolde von Wikullil in Düsseldorf (Figure 2). A sign has been left transparent in the white-painted windowpane and seems to spin along with the circular shape and thus never comes to rest.4 The red and blue tondi in the Stazione II installation (2008) were of a very different nature. They indicated the beginning and end of two long compositions functioning as ‘trains’ in the 50-metre long Field Institute pavilion on the grounds of Museum Insel Hombroich (Figure 3). The white signs in the red and blue tondi seemed to form horizontal syllables, and thus stabilized the circular shape.5 The artist held on to this ordering principle in Stazione IV (2010) in Düsseldorf, where the sky-blue tondi on the walls accompanied a large rust-coloured block in the centre of the exhibition space (Figure 4).6

Figure 3

These first tondi belonged to the architecture or to installations in which Ton Mars combined his earlier pictorial and sculptural spaces with walk-in spaces. Their function was to concentrate the viewers’ attention on the structure of the installations. Meanwhile, as artist in residence at Insel Hombroich, he had already begun working on his Radical Expansions project in 2008, the results of which I now saw on the walls of his studio. In his earlier work, Ton Mars had ‘travelled’ around the world to link his language of signs with geographical, psychological and cultural aspects of reality and thus build his own world in his work.7 In Radical Expansions he exchanged this macro level for the micro level of the physical, chemical and biological processes in nature, and he now associated the circular shape with the living cell that contains all the genetic information, the DNA, of an organism.8 Thus ‘sign cells’ came into being, in which the most important elements leading to potential meanings – the signs – could be transformed through intentional mutations. Already different from a formal point of view, the new project also heralded a phase of reflection. In the Staziones the artist had exchanged the three-dimensionality and the matt surface of his previous painting-objects for flat, reflecting panels in walk-in installations. Now he had also temporarily traded in his works’ cultural orientation for a biological inspiration.

Figure 4

Almost everything seemed to have changed, except for the signs, which stayed firmly rooted. Apparently, they formed the foundation of the work – the ‘soil’ on which everything grew – and this had to be reconfirmed before he could continue. But how was this foundation to function as part of the tondi? Although Ton Mars’s work had always been governed by rules, he designed a new and even stricter algorithm for Radical Expansions. First he designed a ‘sign substrate’ consisting of all major signs he had previously used, thus developing ‘stem signs’ that can evolve into many ‘stem groups’ over several generations. One of the rules he formulated for himself is that the signs within a small tondo (ø 19 cm) should fit into a rectangle, and in such a way that some space remains above and below them and that they can be duplicated in the horizontal direction. By parsing the stem signs, the artist can now generate systematic mutations, in which each subsequent sign combination must preserve some of the character of the original sign. When all possible mutations within a stem group are realized, a wide-ranging and complete ‘biological evolution’ will become visible.9

Since the signs created by Ton Mars always consist of straight lines and partial circles, the circular arcs follow the contours of the tondo while the straight lines oppose them. At the same time, however, the straight lines of the signs and the horizontal orientation of the sign combinations accord with the horizontal parts of the circumscribed square formed by the frame of each small tondo. The colours of a stem group follow from the physical and biological associations accompanying Radical Expansions, since the artist links dark colours – including grey/black, maroon, midnight blue and dark green – with the chaos from which the universe was formed after the Big Bang, and with Earth where life evolves. Ton Mars is still working on the stem groups and, as the mutations grow and mature, the colours of the tondi become brighter, gradually diminishing the contrast between background and signs (Figure 5).

This method resembles the strictly systematic approach of scientific research, but the Radical Expansions project is far removed from this domain. The algorithm mainly guarantees that the work can be continued under any circumstances. Although Ton Mars wants to be systematic and strives for perfection, his work is not scientific or mechanical in nature and does not correspond with a cerebral kind of Concept Art.10 His work method is lucid but remains connected to craftsmanship and it is rooted in spontaneous inspiration. To enjoy the creative flow, Ton Mars alternates times of meticulous planning with periods in which he concentrates solely on the work. Within this self-imposed framework he plans his days as practically as possible, which is necessary because he is a teacher as well as an artist, and has also been a Philosophy student since 2009. His artistic work must thus, of necessity, interfere with these other time-consuming activities. When he has little time, he makes a simple tondo; when he has more time, he can work on a complex composition. He makes small drawings to record what he has already done, so as not to repeat himself. In this way, he still manages to take on this Sisyphean task in a playful and virtually effortless manner.

In addition to being a necessary condition for Ton Mars to continue working, the Radical Expansions project also offers a basis for further innovation in his oeuvre. The signs once evolved from letters and have always retained their link to language and texts, so that the ‘sign substrate’ can lead to new poetic associations. Moreover in art history the tondo has sacral connotations which offers scope for further reflection. As Ton Mars continued to work on Radical Expansions, in 2013 he therefore took up the promises of this project and combined them with new sign combinations he developed earlier.

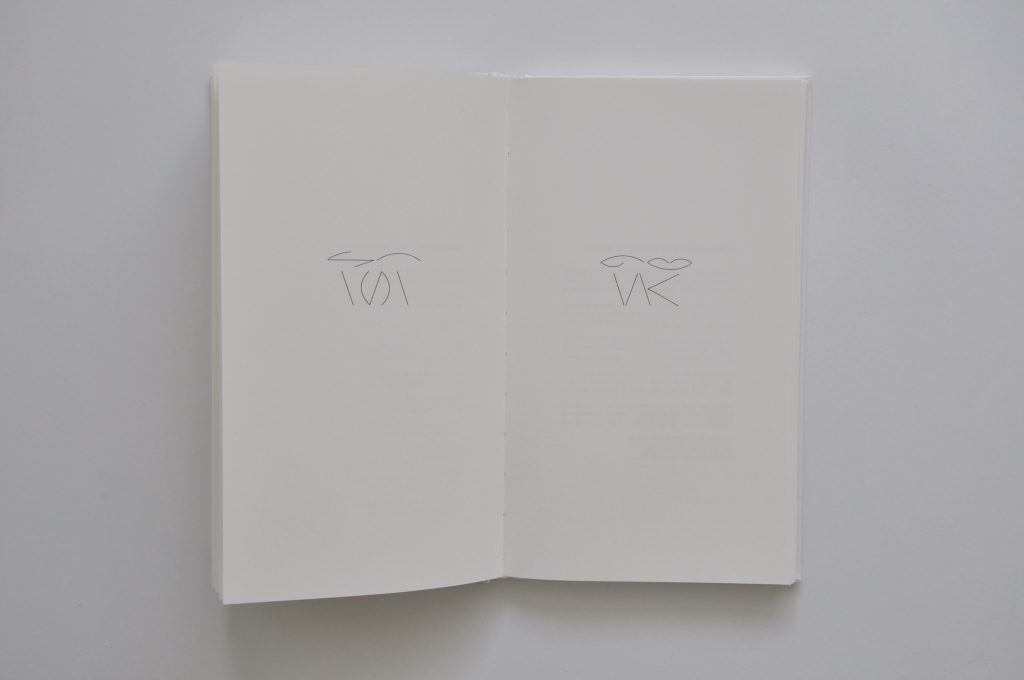

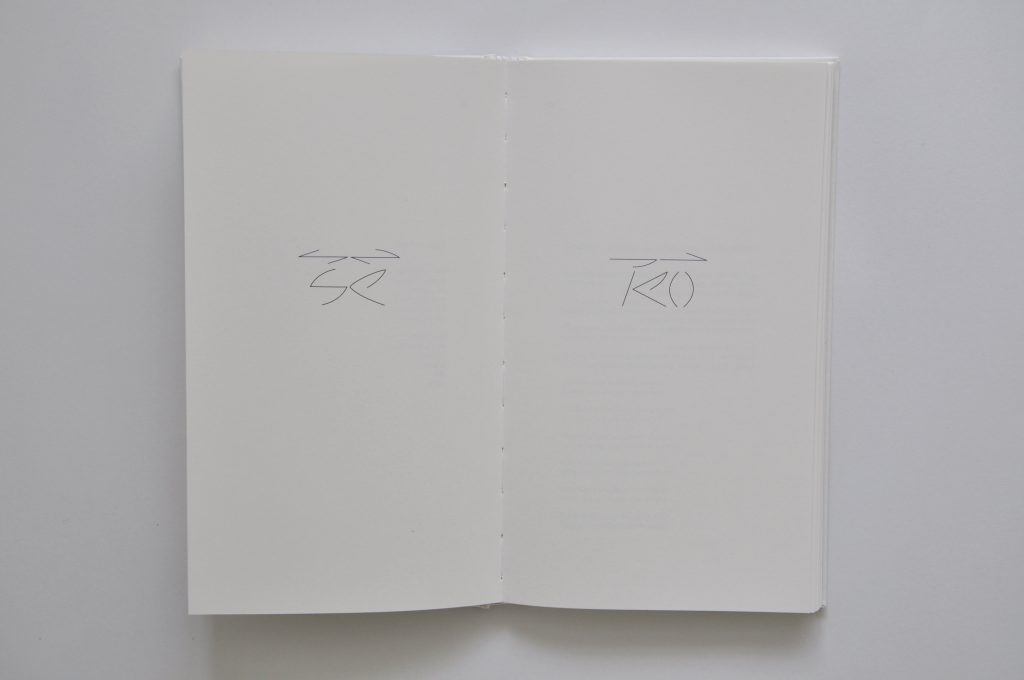

Figure 6

In 2011 he had already contributed fourteen drawings entitled Die Welle und das Wasser to Nachlässiger Nachlass, a collection of poems by Claus A. Froh (Figure 6).11 This series shows sign combinations complemented by what seem to be diacritic marks. In written language such marks guarantee correct pronunciation but Ton Mars never uses ‘real’ letters and words; his work only offers the illusion of readability. Yet his ‘diacritic marks’, too, modify the word-like sign combinations, since their initially horizontal orientation now tends towards the vertical. Such a discovery demands further elaboration, which indeed occurred in 2013 in the From Name to Name project. In his oeuvre those kinds of ideas always arise intuitively: he obeys impulses which lead him to make small sketches. These sketches must then be given a more permanent form to see whether the sign combinations are visually correct. If so, meaningful associations arise. A combination of stem signs with diacritic marks was therefore inscribed in small tondi which formed a ‘word’ or, more precisely, a ‘name’ when laid out horizontally. Soon the artist began to doubt whether such a name was ‘written’ correctly, in other words, whether the series of tondi produced the best ‘typographic’ image.12 For this reason he created ‘improved’ versions of the individual tondi which he alternated above and below the original ‘letters of the name’ (Figure 7). This also gave rise to several innovations in form and content that had not been used in his oeuvre before.

Figure 7

Whereas all previous works by Ton Mars can be ‘read’ as a horizontal line, he now created a multiple cruciform composition with a single horizontal direction and upward and downward vertical directions. A Name can still be read horizontally and the improved, vertically aligned tondi clearly follow from the original line but their signs have become either simpler or more complicated – as happens when a text is improved when the writer begins to doubt a statement or turn of phrase. In philosophy, doubts about the nature of things and the accuracy of statements form the basis of critical thinking. Doubt also stimulates processes in science and art. Yet the traces of such processes are often lost when the doubts fade away as a product or theory is finished.13 However, partly inspired by philosophy, Ton Mars instead exploits his doubts in Names. He openly shows the ambivalences surrounding a work that makes the creative and cognitive processes within art more clearly visible and emotionally understandable to viewers. Thus viewers experience that a product that seems so perfect at first can always be improved, is just one of the possibilities; in other words, that creativity goes on forever .

Just like any other innovation in this oeuvre, The Names also led to fresh associations. Ton Mars is interested in names because of their applications and potential meanings. Although we know that the name of a thing or person usually has no meaning, we always ascribe meanings and even essences to them. We are inclined to think that names and things are inextricably linked, even if names are usually related to things through arbitrary association and force of habit. And the same is true for the names of people. In western countries, children are still often named after saints and/or relatives, but new variations and even completely new names are made up all the time.14 Through habituation, the proper name of individuals gradually comes to coincide with their physical appearance and character, which gives rise to the idea that people’s names express something essential about them. How old this idea is, is illustrated by the biblical passage in which Adam names each creature living in Paradise and thus confirms their ‘existence’ or essence.15 In Ton Mars’s Names we see both the essential and the arbitrary notion of naming. The original horizontal compositions seem to show something essential, while the vertical improvements illustrate that the naming is not ruled by causality.

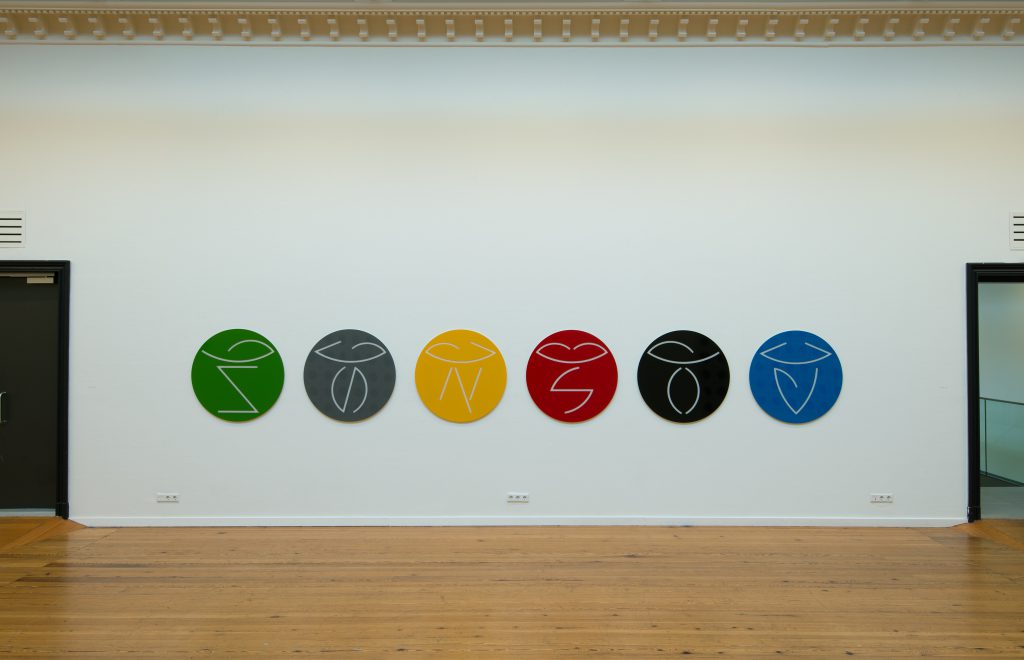

After creating the first two Names, the artist saw that their initial signs were so strong visually that they could also function as separate initials. This led to the creation of the large tondi (ø 95cm, in red, green, black, yellow, blue and taupe), each belonging to a Name (Figure 8). These Initials repeat the ‘first letter’ of a Name but have slightly different colours because the small tondi are painted in matt acrylic paint on watercolor paper, while the large tondi get their colour from being painted with gloss enamel on Perspex.Even more so than the Names, the isolation of the Initials suggests that they are about something essential, with the colours and the diacritic marks confirming the individual nature of each Initial. This corresponds with the use of initials as a person’s monogram or abbreviated signature, while the fact that the artist’s language of signs was once linked to his own initials, TM, gives extra meaning to this new project.16

Figure 8

However, the Initials also have other associations for Ton Mars. Initial letters were given special treatment in medieval book illumination. Sacred books such as the Bible, Evangelions and breviaries were illustrated with scenes from the Scriptures or the lives of saints and were given enlarged and illuminated initials that emphasized the solemn opening of these texts and gave lustre to the sacred nature of the books. ‘Historicized initials’ combined a letter with a miniature and thus functioned as a pictorial table of content of the texts that followed. An initial sometimes grew so large that it became separated from the text and took up an entire page by itself.17 Ton Mars, who is acquainted with such books, for example the Book of Kells (9th century), uses this isolation of initial letters in exhibitions, where he presents The Initials separate from The Names, so that viewers can search for their connection.

This echoing of the old illuminated texts does not mean that the artist strictly links his ‘initial letters’ to the initials in the medieval books. Although his language of signs somewhat resembles hieroglyphics (sacred signs), he has emphatically not designed a sacred but a personal ‘secular’ language.18 However, to further develop his work he does put art history to good use in the Initials in the same way as he uses the form of the tondo in his oeuvre. Although he first became aware of this form when he was commissioned to work on an existing circular window and subsequently assigned the tondo several functions in his installations, Ton Mars is now also inspired by the sacral connotations of tondi.

Circular shapes containing an image were first used on coins, seals and in portraits in Greek and Roman antiquity. The custom continued in the Byzantine era and the Middle Ages, when most tondi depicted Christ or the saints and adorned churches and religious objects. The perfectly circular, eternally rotating form is admirably suited for signifying the absolute, the heavenly, also illustrated in the domes which builders of Christian churches derived from Roman buildings. Sometimes the domes of churches – for example the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem – have an oculus, a circular opening functioning as a window to heaven.19 During the Italian Renaissance the tondo developed into an isolated, fairly large painting often depicting Mary and the Child Jesus or the entire Holy Family. The function of such a tondo is to appeal to the Madonna, for example to grant a couple a child or to beg for the recovery of sick children. Moreover, the Holy Family was the ideal exemplar of relationships within earthly families. This is the reason such tondi were not found in churches but in the private residences of the wealthy, where they sometimes hung over the nuptial bed.20

As it happens, the tondo is not the easiest form for realizing a successful composition. Fifteenth-century artists struggled with this problem and came up with various solutions. Eventually, the compositions became better and better as witnessed by Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo (± 1506), which Ton Mars saw in Florence (Figure 9).21 He noticed that the Holy Family is placed in a square within the circular form. Behind the Holy Family is a horizontal strip, above which the young John the Baptist appears on the right, while further in the background is a frieze of naked youths sitting on or leaning against a rocky wall. This remarkable arrangement stimulated the artist to reflect on the compositions of his own tondi.

Figure 9

The cruciform structure of the Doni Tondo is an echo of fifteenth-century tondi where a landscape or interior is shown behind the Madonna. Yet Michelangelo’s composition is more mature than that of earlier tondi, and this is also related to the iconography of this painting. Mary, representing Mother Earth, is sitting on the ground and receiving the child, placed between heaven and earth, from Saint Joseph. John the Baptist, who will later baptize Jesus, is looking up at him, while the youths probably refer to children who died unbaptized. It was believed that these infants would not go to hell but live, forever young, in limbo (a border place between heaven and hell). Thus the Doni Tondi may have served as a comfort to the Doni couple, who had lost several unbaptized children. With the help of this painting, they could appeal to the heavenly family to protect both their baptized and unbaptized children.22

Figure 10

Figure 11

As was the case with the illuminated books, Ton Mars did not study the iconography of the Doni Tondo before he started working. He is inspired by the formal solutions offered by such historical examples and senses their meanings, which provide ‘material’ and room for reflection about his own work. Using his understanding of the worldly and heavenly connotations of tondi, in 2013 the artist began working on a new series. Celestial Speech is the first in this series and comprises four large tondi (ø 90 cm): two in blue (one in a slightly warmer shade and one in a slightly cooler one), one in black and one in white (Figure 10). In Celestial Speech, he recycles aspects of an earlier project and an earlier work on paper. The latter is The Return (to Blinky Palermo) of 2008, from which the artist derived the signs of Celestial Speech (Figure 11). The former is the beginning of the Ab Uno/Ad Unum project (Eurasia), which he started in 1994 and which contains small diptychs of black and white ‘panels’ with contrasting signs that can be associated with good and evil, light and dark, day and night and other contrasting pairs (Figure 12).23 As in Ab Uno/Ad Unum (Eurasia), the signs in the white and black tondi of Celestial Speech are the direct opposites of their backgrounds, while the signs in the blue tondi remain white as in The Return (to Blinky Palermo). The skylight that lets in different shades of light during the day is linked here with the linguistic nature of the varying signs and with the bright sheen of the tondi.

Figure 12

Earlier work by Ton Mars had surfaces that were intentionally matt. Only in 2007 did he use gloss enamel for the first time, on the panels for his installation Stazione I of 2007 (Figure 13).24 This was mainly inspired by the change from three-dimensional works to two-dimensional panels. In the earlier works ambivalence was created by the combination of the flat facades resembling paintings and the (almost hidden) volume of the objects. Were these paintings or sculptures, and how should they be viewed? In the two-dimensional panels of Stazione I – and the later gloss works – this ambivalence remains but is situated elsewhere. The sheen dematerializes the work, which reflects its environment rather than showing its own material nature. Approaching the work to see what has been inscribed on its attractive lustrous surface does not help. Instead viewers have to step aside to distance themselves from the work and their reflection in it. And again, there is uncertainty about how to relate to this work. Should one look straight at it or cast an oblique glance? Is this about the experience of the literal reflection of the panels or about the mental reflection on the possible meanings of the sign combinations?

Figure 13

The doubt that was so clearly a theme in The Names is present in all of Ton Mars’s work through the various types of ambiguity. The works always require both proximity and distance and offer both a sensual, aesthetic experience and mental activity, an oscillation which has found its present climax in Celestial Speech, since everything in this work contributes to the double – mundane and sublime – connotations: the activities associated with viewing the lustrous tondi, the colours of the earth and sky, the signs with their horizontal row of oblique lines that are stable and the quarter circles rising above them. Returning to the Doni Tondo, we notice that the oblique lines of Celestial Speech remind us of the frieze with the youths behind the Holy Family and that the ascending quarter circles mirror the gesture with which the sitting Mary reaches up towards the Child Jesus. In Ton Mars’s work such echoes can never be regarded as literal quotes, however, although he does seem to have intuitively sensed the worldly and heavenly meanings of the Doni Tondo, also because these play such a major role in his work.25

Although the tondi described here offer new perspectives, it is not just the signs that link them to the rest of the oeuvre. The artist keeps to his chosen path and continues to develop and enrich modern art in both form and content, particularly in its abstract and concrete manifestations.26 To do so, he takes inspiration from many sources, including everyday reality but also linguistics, biology, art history and philosophy. Although Ton Mars has always had an interest in philosophy, his formal studies have helped him to see more clearly the connections between philosophical ideas that he hitherto experienced as fragmented. It is now easier for him to relate a philosophical way of thinking to the artistic principles underlying his work. Moreover, metaphysics serves as a home for his ever-present desire for transcendence. He finds examples of how people used to deal with the transcendent in the religious art of earlier times and links these to the realm of the ‘noumenal’ as defined by Immanuel Kant. This realm is too abstract for our normal way of thinking but it does give rise to ‘regulative ideas’ that foster our thinking and may help to evolve it.27 For, although Ton Mars realizes that we cannot dispense with the mundane, he wants to rise above it and enter suspected but as yet unknown potentialities of reality, aspects of which he hopes and attempts to capture in his work. In Ton Mars’s oeuvre, life and art are thus closely linked; they do not coincide but complement one another.28 Everyday life is given extra impetus by teaching and studying, and the discipline required ensures that the artist can keep on working. The engine driving this combination of life and art, however, is the artist’s longing for transcendence, which stimulates his thinking and makes him search out ever new sources of knowledge and understanding. In each development in his oeuvre Ton Mars completes a circle in which he confirms the basis of his work but also modifies it by incorporating and processing new material for inspiration. Thus he can continue to give viewers opportunities for glimpsing the transcendental, which always seems to slip through our fingers.

Notes:

1. I visited Ton Mars’s studio on 27 September 2013, when we had a conversation that forms the basis of this article. The interpretations of the various works are a joint effort.

2. Since antiquity, the tondo – Italian for ‘circular shape’ – has often been used for portraits. Particularly artists of the Florentine Renaissance frequently used this form, for example Botticelli (± 1445-1510), who painted tondi, and the Della Robbias (15th and 16th centuries), who sculpted tondi. As far as I know, there has never been an artist who exclusively made tondi during some time in his life or for his entire lifetime.

3. The smaller tondi have a diameter of 19 cm, are painted on a square sheet of watercolor paper and framed. With frame, they measure 31 x 31 cm. The tondi are hung on the wall in such a way that the frames are 1 cm apart. The first group of large tondi is The Initials (2013), now including six tondi in red, yellow, blue, green, black and taupe. They are painted with gloss enamel on Perspex and measure 95 cm across. The second group of large tondi is formed by Celestial Speech (2013), a work consisting of four tondi in two shades of blue, black and white. These tondi are also gloss enamel on Perspex, have a diameter of 90 cm and are hung 30 cm apart.

4. A description of Fenster (2003) can be found in K. Herzog ‘De Derde Halte: Hemelsblauw’, 2009. See Ton Mars’s website: www.tonmars.com

5. Stazione II (2008) in Neuss is also described in the above article. The blue and red tondi from this installation are now in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden.

6. A description of Stazione IV (Ort der Schrift), built in 2010 in Düsseldorf, can be found in K. Herzog, ‘The Making of Stazione IV (Ort der Schrift)’, 2010. See Katalin Herzog’s weblog: http://Kunstzaken.blogspot.com.

7. Ton Mars’s metaphorical journey across the world has been described in, inter alia, K. Herzog, ‘Wege ins Zentrum’. See Ton Mars, Echoes & Boundaries, Düsseldorf, Amsterdam 1994, pp. 11-21.

8. Nearly all the terms used by the artist in connection with Radical Expansions originate from cell biology. Thus, ‘sign cells’ refer to the cells of organisms and ‘stem signs’ to stem cells.

9. It is characteristic of Ton Mars that he works on several projects simultaneously. Radical Expansions was started in 2009 and is still far from completion in 2014. However, its ‘yield’ has already inspired new projects such as From Name to Name (which has not been completed either).

10. The type of Concept Art that Ton Mars admires but which he will not pursue is illustrated by the work of Hanne Darboven (1941-2009). She documented her life story in series of numbers and calculations based on the way in which the day, month and year are recorded in the Gregorian calendar.

11. See C. A. Froh, Nachlässiger Nachlass, Gedichte, Filderstadt, Edition Domberger 2011.

12. The image is of primary concern within Ton Mars’s oeuvre, in two respects. First, each work starts out as small sketches that must be visually correct. Secondly, in exhibitions the viewers must first be attracted by the images, which then invite them to reflect.

13. In philosophy, Descartes (1596-1650) used doubt as a method to produce indisputable knowledge. After a session of radical doubt he was left with just two assertions that could not be disputed: ‘I think, therefore I am’ (cogito ergo sum) and ‘God exists’. The process of having doubts and resolving these doubts is often explicitly shown in art, while scientists often omit it in their research findings.

14. In Europe, names traditionally given to children have been replaced by abbreviations, contractions and American names denoting places (Dakota), professions (Taylor) or substances (Amber). Children are sometimes also named after celebrities or famous persons (Chanel). This clearly illustrates the arbitrary nature of name-giving; however, such names do have social functions.

15. See Genesis 2:18-20, Bible, Authorized Version (KJV). See also D. Kaufmann, ‘Adorno and the Name of God’, http://webdelsol.com/FLASHPOINT/adorno.htm.

16. From as early as 1983, when he saw the letters TM – his initials – in the structure of a chair, Ton Mars has been developing a language of signs based on shapes derived from furniture. In 1987 he gave the signs their present letter-like form.

17. See H. Brandhorst, ‘Initiaal’, http://collecties.meermanno.nl/handschriften/initiaal. When Ton Mars started The Initials, he looked at reproductions of pages from the Book of Kells. On his travels he has also seen other illuminated manuscripts in various museums.

18. Ton Mars developed his signs by analogy with the western alphabet. They only resemble hieroglyphics in the sense that they are unintelligible, which hieroglyphics were also thought to be before Champollion deciphered them in 1824.

19. In Roman architecture, both bathhouses and temples had domes. In the bathhouses, the opening in the dome served as a steam vent. An example of a temple with a dome is the Pantheon in Rome (originally built in 27 BC). The Pantheon’s dome contains an oculus (eye) which provides access to sunlight and rain. The dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (1149) has an oculus surrounded by a relief of sunbeams, which refers to Christ as the light of the world. It is believed that this church was built on the site where Christ was crucified and buried.

20. R. J. M. Olson, ‘Lost and Partially Found: The Tondo, a Significant Florentine Art Form, in the Documents of the Renaissance.’ See Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 14, No. 27, 1993, pp. 31-65.

21. The panel of the Doni Tondo (± 1506) has a diameter of 120 cm. The original frame has a diameter of 172 cm. The work is held by the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

22. C. Franceschini, ‘The Nudes in Limbo: Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo Reconsidered’. See Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, LXXIII, 2010, pp. 137-180.

23. The start of the Ab Uno/Ad Unum project is documented in K. Herzog, ‘De twee die een genoemd is’. See Ton Mars & Katalin Herzog, Ab Uno/Ad Unum, Groningen 1998, pp. 19-29. The 2002 NEUNG (Thai-language) diptych, which is shown here as an example of part of this project (viz. Eurasia), measures 32 x 24 x 10 cm per panel and is in the collection of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden. The four-part work The Return (to Blinky Palermo) of 2008, of which each element measures 31 x 31 cm (including frame), is in the same collection.

24. The Stazione I installation was constructed in 2007 in Galerie Cora Hölzl, Düsseldorf. A description of Stazione I has been published in K. Herzog, ‘De Derde Halte: Hemelsblauw’, 2009. See Ton Mars’s website: www.tonmars.com

25. That this is not a literal quote is also evident from the fact that the signs in Celestial Speech originate from The Return (to Blinky Palermo). Still, this is not the first time that Ton Mars has had such an intuitive connection with works of art from the past. This is documented in K. Herzog, ‘Voor Dansers, een interpretatie van de triptiek Winner, Saviour, Loser van Ton Mars’ (1994). See Feit & Fictie, Vol. III, nr. 3, 1997, pp. 67-82.

26. Ton Mars has always felt a connection with abstract art but he has never accepted the formalism and materialism that follow from it. He wanted to develop abstract art from the point where Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) left off. Like Mondrian, he combines the visual language of abstract art with symbolism but he is also open to other developments in contemporary art.

27. In his book Kritik der reinen Vernunft (1781), Kant defined two domains of knowledge: the ‘phenomenal’ and the ‘noumenal’. The first domain, of the experiences, can be acknowledged through the senses. The raw data provided by the senses must subsequently be processed with the help of mental categories such as space and time. The second domain, the transcendental (not a term used by Kant), cannot be entered into through observation and mental activity but may be accessed through reason and faith. This gives us the ability to generate the ‘regulative ideas’ denoting, inter alia, abstractions with which to summarize knowledge and evolve our thinking.

28. Making life and art converge was an important goal of the early avant-garde who did not want to fuse art and life so much as recreate life to match art. See P. Bürger, Theorie der Avantgarde, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp 1974. Like the avant-garde artists, Ton Mars sees art as a utopia, a counterpart to every-day reality. However, he is aware that in today’s world where such elevated ideals have become problematic, life cannot be transformed to resemble art. Nevertheless, as a ‘traveller between earth and heaven’, in his work he wants to keep alive the original autonomous function of art as a vehicle of the possible.